Yesterday, I went to a pharmacy and picked up some prescription medication.

Not really a notable thing in itself, except that this medication was estrogen, prescribed for the purpose of physical feminisation.

This… has taken a while. Let’s see how we got here.

The timeline so far

2012 to 2013-ish: Engaged in little of the ol’ gender exploration, briefly identifying as agender and using any pronouns. At this time, I was already using a name different from what I was given at birth: Grey.

March 2014: Started identifying as a woman within close friend circles. Began going by the name Kimberly and using she/her pronouns in those circles.

June 2014: First attempt to get a referral to an NHS gender identity clinic (GIC).

July 2014: Came out as a transgender womanit. Wore women’s clothing outside for the first time. Faced harrassment from random members of the public basically immediately.

August 2014: Came out to family members. Things started well, then went less well.

March 2015: Came out to work colleagues.

August 2015: Changed legal name to Kimberly Grey.

August 2016: Asked my new GP (general practioner; I think they call them “family doctors” in the US) if there’d been any news from the GIC. Learned that the previous GP had done things incorrectly and hadn’t referred me to a GIC at all. Second attempt to get a referral to an NHS GIC.

October 2016: Received confirmation of my referral to the West of England Gender Identity Clinic.

December 2020: Having not heard anything for four years (the original estimate was 18 months), I got in contact with a private doctor.

January 2021: Following a short assessment, I was diagnosed with “gender incongruence” by the private doctor. Began steps to acquire hormone replacement therapy (HRT) via a private endocrinologist, but administrative complications happened and my anxiety caused me to abandon the attempt.

April 2022: Began self-medicating HRT, with hormones and anti-androgens purchased from foreign pharmacies.

July 2022: Underwent a bit of an identity crisis, starting to identify as alterhuman, changing my preferred name to beeps, returning to identifying as agender, and beginning to use it/its pronouns.

August 2022: After several years without any form of valid ID, I finally got a passport issued with my new name and an updated gender marker.

December 2023: Finally got contacted by the GIC to organise my first appointment.

February 2024: First appointment. This was a clinical assessment that asked basic questions about my background & my physical and mental health.

July to September 2024: Had a total of six two-hour appointments with a psychiatrist doing a deep dive into my history of gender identity, sexuality, relationships, upbringing, relationships and mental wellbeing.

October 2024: Received a final clinical report detailing everything discussed in the previous appointments, ultimately agreeing with the previous diagnosis of gender incongruence and recommending that I be prescribed feminising hormone therapy.

Late November 2024: Had an appointment with a doctor specialising in transgender healthcare to discuss the details of the desired treatments and to agree on what referrals to third-parties we wanted to pursue.

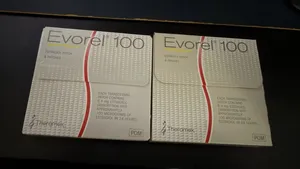

Late December 2024: Assigned a ‘named professional’, who is my liaison with the GIC going forward, and received a prescription for estrogen patches.

For those not keeping track, that’s more than eight years between the initial gender clinic referral and the start of any form of treatment. By original estimates, this should have been less than three years. It’s been 10 years since I first tried to get a referral, and over 12 years since I first started exploring my gender identity.

For someone in the NHS gender clinic system, that’s how long it can take just to get to square one of medical transition.

That was not the start of this story. That was the prologue.

The opinion zone

I doubt anyone with any real sway in the government or NHS will read this, but I have some thoughts as to how this whole process could be made way better for the people on the receiving end.

If you think that this is wandering into forbidden political territory, it isn’t. Transgender lives and experiences aren’t your political pawns. Fuck off with that.

Please for the love of god, fix wait times

As it stands, the wait times are obscenely long.

These wait times kill people.

These wait times drive people (like me!) to acquire prescription drugs from dodgy websites.

These wait times make the possibility of medical transition less likely for the people waiting for it, as there are greater medical risks of starting HRT above a certain age, and it is typical that starting sooner produces more noticeable changes.

This is why folks who argue that the existing barriers to accessing gender-affirming healthcare are too lax are talking bullshit.

Nobody who successfully makes it to being a GIC patient is ‘going through a phase’ or doing it just for the fun of it. It’s annoying, and stressful, and upsetting, and you’re left for years to wallow in your own thoughts and feelings before you ever get to speak to a specialist.

And let me reiterate, the ones who don’t successfully make it are often dead.

By the time you’re actually attending appointments at a GIC, you’ve already had years to figure out and lock down what you want.

This, by a significant margin, is the single biggest failure of the gender clinic system. The wait times have to come down.

Improve training across the board

A major delay in my transition was that the first GP I approached for a referral simply didn’t know how to do one. They did it wrong. I didn’t hear anything from any part of the NHS and simply had no idea what had happened until I changed GP and tried again a couple of years later.

Although not an issue I’ve encountered, many GPs are beginning to refuse the shared care agreements with GICs on the (flawed) basis that they do not have the necessary training to treat trans people, and thus can refuse to do so on safety grounds.

GICs are required to use shared care agreements when recommending treatment plans, as they are actively forbidden from issuing their own prescriptions. For a patient, their GP refusing a shared care agreement can completely prevent any access to gender-affirming healthcare.

Both of these things should not happen, they should never happen. And both are the result of GPs not knowing how to interact with GICs and what their obligations are when it comes to actioning treatment plans for transgender patients.

I’m not going into detail yet as it’s an unresolved situation, but I currently only have estrogen prescribed, because my GP refused to prescribe the GIC’s recommended anti-androgen.

Even with a GP that has been very cooperative with the gender clinic, there are these annoying hurdles seemingly introduced by a lack of trust or understanding.

I, personally, had a very pleasant experience with the staff at my gender clinic, all of whom were professional, compassionate, knowledgeable, and clearly doing their best with limited resources and uncomfortable levels of scrutiny. They made every effort to ensure I was comfortable and that accommodations were available for my anxiety-ridden, neurodivergent ass, although I ultimately never needed any of them.

I’ve heard lots of stories that this isn’t consistent between clinics, and that some staff are rude, dismissive, and probing in uncomfortable ways.

This is obviously unhelpful when dealing with patients who are already frequent subjects of abuse and derision both personally and from the media. It fosters hostility and distrust in the gender clinic system, and this negative reputation precedes many people’s actual first interactions with it.

It feels like medical professionals having empathy for their patients shouldn’t be a high bar, but it’s one that, anecdotally, many GIC staff fail to reach.

Consider introducing treatments by informed consent

Ultimately, I believe that the gender clinic system shouldn’t really exist, at least not in its current form.

By its nature, it’s a form of gatekeeping.

Imagine if you had to convince a series of priests that you were a Christian before you were ever allowed to participate in mass? Wearing a cross and quoting scripture isn’t good enough, rote knowledge and external symbols are proof of research, not proof of your spiritual belief.

You can’t ever objectively prove you’re a Christian, so any demands that you do so are mere gatekeeping.

The same is true of the GICs. It’s a system that demands that you prove the existence of something that cannot be objectively observed, over and over again, to a series of complete strangers. Whether wearing a dress and discussing a disjointed sense of self ‘counts’ or not depends entirely on who you’re talking to. It’s just gatekeeping.

The answer to this problem and pretty much all of the ones previously described is permitting hormone replacement therapy by informed consent.

Informed consent removes gatekeeping, it removes wait times, it removes the need for GPs to be specifically trained in dealing with transgender patients, and it removes the requirement for repeated, sometimes-unpleasant appointments.

Informed consent removes these barriers by putting the onus of a sensible, healthy application of HRT in the hands of the patient, rather than doctors.

“But beeps,” you may be asking, “Doesn’t removing those barriers put patients at unnecessary medical risk?”

Bombshell moment incoming…

GICs already require informed consent before prescribing hormone replacement therapy.

This is because there aren’t any drugs in the UK that are approved for transgender HRT. All HRT used in this fashion is prescribed ‘off-label’, and requires individual, informed consent from the intended recipient before a prescription will be issued.

I’m not arguing for the abolition of the gender clinic system. Having a specialist to talk to and receive guidance from is incredibly helpful, but it really feels like these should be optional and accessed at the patient’s discretion rather than being a hard requirement.

Some sort of pre-assessment before surgical procedures take place also makes sense to keep, but this is already true of all non-emergency surgeries.

Informed consent isn’t a new idea, in fact, many of the UK’s political allies already have it, including the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, and many of the countries in western Europe.

The UK not providing the option remains a regressive choice, yet another feather in the cap of “TERF Island”, and that desperately needs to change.